- Home

- Anne Glenconner

Lady in Waiting

Lady in Waiting Read online

Copyright

Copyright © 2020 by Anne Glenconner

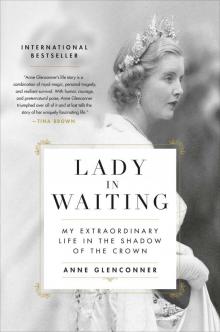

Cover design by Terri Sirma

Cover photograph © Mirrorpix/Getty Images

Cover copyright © 2020 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

Hachette Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10104

HachetteBooks.com

Twitter.com/HachetteBooks

Instagram.com/HachetteBooks

Originally published in hardcover and ebook by Hodder & Stoughton in Great Britain in October 2019

First US Edition: March 2020

Published by Hachette Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Hachette Books name and logo is a trademark of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019951170

ISBNs: 978-0-306-84636-6 (hardcover), 978-0-306-84635-9 (ebook)

E3-20200213-JV-NF-ORI

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

1: The Greatest Disappointment

2: Hitler’s Mess

3: The Traveling Salesman

4: The Coronation

5: For Better, For Worse

6: Absolutely Furious

7: The Making of Mustique

8: A Princess in Pajamas

9: Motherhood

10: Lady in Waiting

11: The Caribbean Spectaculars

12: A Royal Tour

13: A Year at Kensington Palace

14: The Lost Ones

15: A Nightmare and a Miracle

16: Forever Young

17: The Last Days of a Princess

18: Until Death Us Do Part

19: Whatever Next?

Photos

Acknowledgments

Picture Acknowledgments

Discover More

More praise for LADY IN WAITING

For my children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

PROLOGUE

ONE MORNING AT the beginning of 2019, when I was in my London flat, the telephone rang.

“Hello?”

“Lady Glenconner? It’s Helena Bonham Carter.”

It’s not every day a Hollywood film star rings me up, although I had been expecting her call. When the producers of the popular Netflix series The Crown contacted me, saying that I was going to be portrayed by Nancy Carroll in the third season, and that Helena Bonham Carter had been cast as Princess Margaret, I was delighted. Asked whether I minded meeting them so they could get a better idea of my friendship with Princess Margaret, I said I didn’t mind in the least.

Nancy Carroll came to tea, and we sat in armchairs in my sitting room and talked. The conversation was surreal as I became extremely self-aware, realizing that Nancy must be absorbing what I was like.

A few days later when Helena was on the telephone, I invited her for tea too. Not only do I admire her as an actress but, as it happens, she is a cousin of my late husband Colin Tennant, and her father helped me when one of my sons had a motorbike accident in the eighties.

As Helena walked through the door, I noticed a resemblance between her and Princess Margaret: she is just the right height and figure, and although her eyes aren’t blue, there is a similar glint of mischievous intelligence in her gaze.

We sat down in the sitting room, and I poured her some tea. Out came her notebook, where she had written down masses of questions in order to get the measure of the Princess, “to do her justice,” she explained.

A lot of her questions were about mannerisms. When she asked how the Princess had smoked, I described it as rather like a Chinese tea ceremony: from taking her long cigarette holder out of her bag and carefully putting the cigarette in, to always lighting it herself with one of her beautiful lighters. She hated it when others offered to light it for her, and when any man eagerly advanced, she would make a small but definite gesture with her hand to make it quite clear.

I noticed that Helena moved her hand in the tiniest of reflexes, as if to test the movement I’d just described, before going on to discuss Princess Margaret’s character. I tried to capture her quick wit—how she always saw the humorous side of things, not one to dwell, her attitude positive and matter-of-fact. As we talked, the descriptions felt so vivid, it was as though Princess Margaret was in the room with us. Helena listened to everything very carefully, making lots of notes. We talked for three hours, and when she left, I felt certain that she was perfectly cast for the role.

Both actors sent me letters thanking me for my help, Helena Bonham Carter expressing the hope that Princess Margaret would be as good a friend to her as she was to me. I felt very touched by this and the thought of Princess Margaret and I being reunited on-screen was something I looked forward to. I found myself reflecting back on our childhood spent together in Norfolk, the thirty years I’d been her Lady in Waiting, all the times we had found ourselves in hysterics, and the ups and downs of both our lives.

I’ve always loved telling stories, but it never occurred to me to write a book until these two visits stirred up all those memories. From a generation where we were taught not to overthink, not to look back or question, only now do I see how extraordinary the nine decades of my life have really been, full of extreme contrasts. I have found myself in a great many odd circumstances, both hilarious and awful, many of which seem, even to me, unbelievable. But I feel very fortunate that I have my wonderful family and for the life I have led.

CHAPTER ONE

The Greatest Disappointment

HOLKHAM HALL COMMANDS the land of North Norfolk with a hint of disdain. It is an austere house and looks its best in the depths of summer when the grass turns the color of demerara sugar so the park seems to merge into the house. The coast nearby is a place of harsh winds and big skies, of miles of salt marsh and dark pine forests that hem the dunes, giving way to the vast stretch of the gray-golden sand of Holkham beach: a landscape my ancestors changed from open marshes to the birthplace of agriculture. Here, in the flight path of the geese and the peewits, the Coke (pronounced “cook”) family was established in the last days of the Tudors by Sir Edward Coke, who was considered the greatest jurist of the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras, successfully prosecuting Sir Walter Raleigh and the Gunpowder Plot conspirators. My family crest is an ostrich swallowing an iron horseshoe to symbolize our ability to digest anything.

There is a photograph of me, taken at my christening in the summer of 1932. I am held by my father, the future 5th Earl of Leicester, and surrounded by male relations wearing solemn faces. I had tried awfully hard to be a boy, even weighing eleven pounds at birth, but I was a girl and there was nothing to be done about it.

My female status meant that I would not inherit the earldom, or Holkham, the fifth largest estate in England with its 27,000 acres of top-grade agricultural land, neither the furniture, the books, the paintings, nor the silver. My parents went on to hav

e two more children, but they were also daughters: Carey two years later and Sarah twelve years later. The line was broken, and my father must have felt the weight of almost four centuries of disapproval on his conscience.

My mother had awarded her father, the 8th Lord Hardwicke, the same fate, and maybe in solidarity, and because she thought I needed to have a strong character, she named me Anne Veronica, after H. G. Wells’s book about a hardy feminist heroine. Born Elizabeth Yorke, my mother was capable, charismatic, and absolutely the right sort of girl my grandfather would have expected his son to marry. She herself was the daughter of an earl, whose ancestral seat was Wimpole Hall in Cambridgeshire.

My father was handsome, popular, passionate about country pursuits, and eligible as the heir to the Leicester earldom. They met when she was fifteen and he was seventeen, during a skiing trip in St. Moritz, becoming unofficially engaged immediately, he apparently having said to her, “I just know I want to marry you.” He was also spurred on by being rather frightened of another girl who lived in Norfolk and had taken a fancy to him, so he was relieved to be able to stop her advances by declaring himself already engaged.

My mother was very attractive and very confident, and I think that’s what drew my father to her. He was more reserved so she brought out the fun in him and they balanced each other well.

Together, they were one of the golden couples of high society and were great friends of the Duke and Duchess of York, who later, because of the abdication of the Duke’s brother, King Edward VIII, unexpectedly became King and Queen. They were also friends with Prince Philip’s sisters, Princesses Theodora, Margarita, Cecilie, and Sophie, who used to come for holidays at Holkham. Rather strangely, Prince Philip, who was much younger, still only a small child, used to stay with his nanny at the Victoria, a pub right next to the beach, instead of at Holkham. Recently I asked him why he had stayed at the pub instead of the house, but he didn’t know for certain, so we joked about him wanting to be as near to the beach as possible.

My parents were married in October 1931 and I was a honeymoon baby, arriving on their first wedding anniversary.

Up until I was nine, my great-grandfather was the Earl of Leicester and lived at Holkham with my grandfather, who occupied one of the four wings. The house felt enormous, especially seen through the eyes of a child. So vast, the footmen would put raw eggs in a bain-marie and take them from the kitchen to the nursery: by the time they arrived, the eggs would be perfectly boiled. We visited regularly and I adored my grandfather, who made an effort to spend time with me: we would sit in the long gallery, listening to classical music on the gramophone together, and when I was a bit older, he introduced me to photography, a passion he successfully transferred to me.

With my father in the Scots Guards, a regiment of the British Army, we moved all over the country, and I was brought up by nannies, who were in charge of the ins and outs of daily life. My mother didn’t wash or dress me or my sister Carey; nor did she feed us or put us to bed. Instead, she would interject daily life with treats and days out.

My father found fatherhood difficult: he was straitlaced and fastidious and he was always nagging us to leave our bedroom windows open and checking to make sure we had been to the lavatory properly. I used to struggle to sit on his knee but because I was too big he would push me away in favor of Carey, whom he called “my little dolly daydreams.”

Having grown up with Victorian parents, his childhood was typical of a boy in his position. He was brought up by nannies and governesses, sent to Eton and then on to Sandhurst, his father making sure his son knew what was expected of him as heir. He was loving, but from afar: he was not affectionate or sentimental, and did not share his emotions. No one did, not even my mother, who would give us hugs and show her affection but rarely talked about her feelings or mine—there were no heart-to-hearts. As I got older she would give me pep talks instead. It was a generation and a class who were not brought up to express emotions.

But in many other ways my mother was the complete opposite of my father. Only nineteen years older than me, she was more like a big sister, full of mischief and fun. Carey and I used to shin up trees with her and a soup ladle tied to a walking stick. With it, we would scoop up jackdaws’ eggs, which were delicious to eat, rather like plovers’. Those early childhood days were filled with my mother making camps with us on the beach or taking us on trips in her little Austin, getting terribly excited as we came across ice-cream sellers on bicycles calling, “Stop me and buy one.”

The epitome of grace and elegance when she needed to be, she also had the gumption to pursue her own hobbies, which were often rather hands-on: she was a fearless horsewoman and rode a Harley-Davidson. She passed on her love of sailing to me. I was five when I started navigating the nearby magical creeks of Burnham Overy Staithe in dinghies, and eighty when I stopped. I used to go in for local races, but I was quite often last, and would arrive only to find everyone had gone home.

Holkham was a completely male-oriented estate and the whole setup was undeniably old-fashioned. My great-great-grandfather, the 2nd Earl, who had inherited his father’s title in 1842 and was the earl when my father was a boy, was a curmudgeon and so set in his ways that even his wife had to call him “Leicester.” When he was younger, he apparently passed a nurse with a baby in the corridor and asked, “Whose child is that?”

The nurse had replied, “Yours, my lord!”

A crusty old thing, he had spent his last years lying in a trundle bed in the state rooms. He wore tin-framed spectacles, and when he went outside, he would go around the park in a horse-drawn carriage, with his long-suffering second wife, who sat on a cushion strapped to a mudguard.

Influenced by the line of traditional earls, Holkham was slow to modernize, keeping distinctly separate roles for the men and women. In the summer, the ladies would go and stay in Meales House, the old manor down by the beach, for a holiday known as “no-stays week” when they quite literally let their hair down and took off their corsets.

From when I was very little, my grandfather started to teach me about my ancestors: about how Thomas Coke, 1st Earl of Leicester in its fifth creation (the line had been broken many times, only adding to the disappointment of my father at having no sons), had gone off to Europe on a grand tour—the equivalent of an extremely lavish gap year—and shipped back dozens of paintings and marble statues from Italy that came wrapped in Quercus ilex leaves and acorns, the eighteenth-century answer to bubble wrap.

He told me all about when the ilex acorns were planted, becoming the first avenue of ilex trees (also called holm oak, a Mediterranean evergreen) in England. My grandfather’s father had sculpted the landscape, pushing the marshes away from the house by planting the pine forests that now line Holkham beach. Before him, the 1st Earl in its seventh creation became known as “Coke of Norfolk” because he had such a huge impact on the county through his influence on farming—he was the man credited with British agricultural reform.

Life at Holkham continued to revolve around farming the land, all elements of which were taken seriously. As well as dozens of tenant farmers, there were a great many gardeners to look after the huge kitchen garden. The brick walls were heated with fires all along, stoked through the night by the garden boys, so nectarines and peaches would ripen sooner. On hot summer days I loved riding my bike up to the kitchen gardens, being handed a peach, then cycling as fast as I could to the fountain at the front of the house and jumping into the water to cool down.

Shooting was also a huge part of Holkham life, and really what my father and all his friends lived for. It was the main bond between the Cokes and the Royal Family, especially with the royal estate of Sandringham only ten miles away—a mere half an hour’s drive. Queen Mary had once rung my great-grandmother, suggesting she come over with the King, only for my great-grandfather to be heard bellowing, “Come over? Good God, no! We don’t want to encourage them!”

My father shot with the present Queen’s father, King Georg

e VI, and my great-grandfather and grandfather with King George V on both estates, but it was Holkham that was particularly famous for shooting: it held the record for wild partridges for years and it’s where covert shooting was invented (where a copse is planted in a round so that it shelters the game, the gun dogs flushing out the birds gradually, allowing for maximum control, making the shoot more efficient).

It was also where the bowler hat was invented: one of my ancestors had got so fed up with the top hat being so impractical that he went off to London and ordered a new type of hat, checking how durable it was by stamping and jumping on it until he was content. From then on gamekeepers wore the “billy coke,” as it was called then.

There were other royal connections in the family too. It is well documented that Edward, Prince of Wales, later King Edward VIII, had many love affairs with married, often older glamorous aristocrats, the first being my paternal grandmother, Marion.

My father was Equerry, an attendant to the Duke of York, and his sister, my aunt Lady Mary Harvey, was Lady in Waiting to the Duchess of York after she became Queen. When the Duke of York was crowned King George VI in 1937, my father became his Extra Equerry; and in 1953 my mother became a Lady of the Bedchamber, a high-ranking Lady in Waiting, to Queen Elizabeth II on her Coronation.

My father especially was a great admirer of the Royal Family and was always very attentive when they came to visit. My earliest memories of Princess Elizabeth and Princess Margaret come from when I was two or three years old. Princess Elizabeth was five years older, which was quite a lot—she was rather grown-up—but Princess Margaret was only three years older and we became firm friends. She was naughty, fun, and imaginative—the very best sort of friend to have. We used to rush around Holkham, past the grand pictures, whirling through the labyrinth of corridors on our trikes or jumping out at the nursery footmen as they carried huge silver trays from the kitchen. Princess Elizabeth was much better behaved. “Please don’t do that, Margaret,” or “You shouldn’t do that, Anne,” she would scold us.

Lady in Waiting

Lady in Waiting